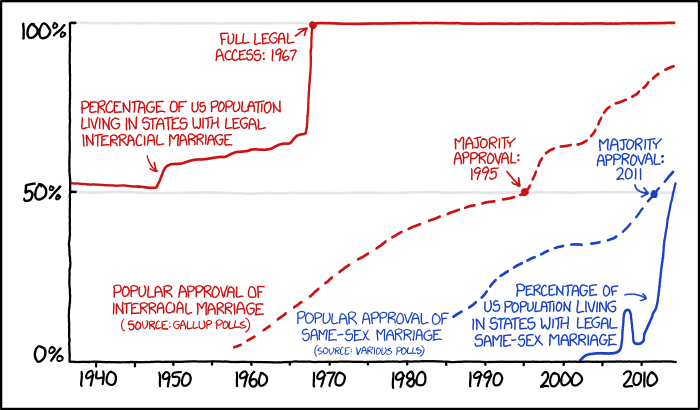

A few days ago, a student referred me to the following graph:

The graph raises two questions for me. The first and most glaring question is the gap between the red lines, between public opinion on interracial marriage and the percentage of people who lived in states that allowed the practice. To be sure, this explains Naim v. Naim and the Court's refusal to strike down anti-miscegenation laws as discordant with Brown and equal protection. But what it does not explain is the Court's decision in Loving, which struck down these laws in the 16 states that still had laws in the books against interracial marriage. It seems the case cannot be explained by pointing to public opinion in 1967. It also cannot be explained as a time when the Court rounded up a few remaining outliers.

Could the case be explained by invoking morality and constitutional principles? If not, what is left?

The second question focuses on the lag between opinion on marriage equality the number of states approving the practice. That the blue lines are about to meet sometime soon tells us something important about the rapidity with which the marriage equality debate has moved in the last few years. To me, the question is: what accounts for that change? Can we explain it simply by pointing to social movement theory?

This leads me to a third question, about which I will have much more to say in a future post: why did the Court hesitate last week and decide against entering the marriage equality debate? To enter the debate would be to side with a majority of the American public. It is also true that a majority of the population now live in states that issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The writing is clearly on the wall. So why wait? How strong must public opinion be on this question? How many outliers must remain?

Part of the answer must be that we misunderstand what the Court is, what it does, and what it can do. We have a romantic view, fostered by the media and taught in many law schools, of the Court as a countermajoritarian hero. This is not an accurate view of the Court and its work. The Court is far from a fearless defender of the rights of minorities. In fact, the Court seldom leads public opinion but follows it. Rather than looking at the Court's hesitation from last week and asking why it chose not to decide, the better question is: how much more will it take for the Court to get in the marriage equality debate?

Friday, October 17, 2014

Saturday, October 11, 2014

The Court on Gay Marriage

Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear appeals from five states that sought to ban gay marriage. The Court also declined to explain why. This led supporters of gay marriage to hail the Court's non-action. But not everyone agreed that this was a good thing.

Critics made the obvious arguments. According to Professor John C. Eastman, it was “beyond preposterous” for federal courts to define marriage. This was a question that must be left to the political process. But what would he make of the Court's view, expressed in 1967, that "[t]he freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men"? Or the recognition that "[m]arriage is one of the 'basic civil rights of man,' fundamental to our very existence and survival." The case was Loving v. Virginia.

I also wonder what he might say about the Supreme Court short-circuiting the political process in Shelby County. I wonder.

Progressives also were not unanimous in their approval. One argument in particular caught my attention. This was from Slate's Dahlia Lithwick:

Regardless of the answers, the court should not be in the business of gingerly surfing public opinion until it’s safe enough to ride that wave into shore. And by waiting (or even talking publicly about thinking about waiting) for the majority of Americans to climb on board before ruling, the court is failing at its most vital task: protecting civil liberties from majorities not inclined to wait. The court hardly becomes more legitimate by suggesting that it will decisively do the right thing once it’s been done. And as of Monday, it’s been done.Lithwick is asking the Court to play the role of countermajoritarian hero. But we must ask, has the Court ever played this role in American history? This is a game I often play with my students: think of a case when the Court in fact played this role, and let's think about how it was possible. Brown is often the first answer they think of, and it is often the only one. They don't often think of Brown II, or Naim v. Naim, or Eisenhower and the Little Rock Nine, or the March on Washington, or Freedom Summer. rather, they think of Brown in a vacuum. And that is not only misguided, but it is also a mythology of the Court that we should not foster.

Think of this: could we view the Court inevitable reconsideration of the Second Reconstruction as an instance when the Court will be performing "its most vital task"? I suspect that Professor Eastman would encourage the Court to do precisely that. And if so, what does that tell us about the Court's role? Could our perceptions be clouded by nothing as crass as whose ox is being gored?

College Board, AP Testing, and Ideology

I must begin with a confession: I am not a fan of standardized tests. I am also not a fan of the College Board, or of AP classes in general. That said, I have followed with great interest the debate in Colorado over curricular changes in AP American history courses. A few days ago, an entry from the N Y Times editorial page editor's blog included a link to a full practice test based on the new AP curriculum. And yes, I got curious.

The questions were fairly bland and straight-forward. Nothing really jumped out at me (though maybe that's the point, a critic might argue). Until I came to page 13.

Labels:

AP History,

College Board,

Colorado school board

Friday, October 10, 2014

As Hobby Lobby Collides with the End of the Second Reconstruction Through the Fair Housing Act

A week ago, the Court granted cert in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, Inc. The case involves a challenge to the allocation of low-income housing tax credits under the Fair Housing Act. The narrow question for the Court is whether the Fair Housing Act recognizes disparate impact claims. But a far more important and far-reaching question lies in the background of the case: what is the constitutional status of disparate-impact claims?

Put this way, this question takes me to the end of last Term and Hobby Lobby. While the case was hailed at the time as either a victory for religious freedom or an attack on women's health care, a crucial aspect of this debate has gone almost unnoticed: how Justice Alito's opinion for the Court appears to short-circuit the ongoing conservative project to end the Second Reconstruction.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)