Three days ago, the college football selection committee finalized its final four choices to take part in the first annual playoff to determine the sports national champion. The University of Oregon and and the University of Alabama were certain to make it, but the other two choices were a bit more controversial. Critics of Florida State University argued that, though undefeated, FSU played a soft schedule and escaped from defeat myriad times this season. The fourth choice, Ohio State University, was even more surprising. Never in the time I have watched college football do I remember a time when a team jumps those above it in any type of ranking, whether traditional polls or BCS rankings, after all the relevant teams win their final games. Ohio State destroyed Wisconsin, to be sure, but Baylor and TCU similarly won their games. And yet Ohio State made it into the playoffs. And the debates began.

I watched these developments with great amusement. I wondered whether anybody else could see the connection between this so very public debate and the use of race in employment, college admissions, and elsewhere.

The similarities are astounding. And it makes clear that the affirmative action debate should be more like the college football selection process. But there is no chance of that. When it comes to race, reason and judgment leave us, and stupid sets in.

Thursday, December 11, 2014

Sunday, November 2, 2014

The Road from Texas to the End of the Second Reconstruction through the FHA

On October 2, the Court granted cert on a deceptively simple question: whether disparate impact claims are cognizable under the Fair Housing Act. The case is Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, Inc. This is the Court's third attempt since 2012 to answer this question, having granted cert in two prior cases, only to see the parties settle their disputes before the Court could answer it. The most recent case, Twp. Of Mount Holly v. Mt. Holly Gardens Citizens in Action, Inc., was dismissed on November 15, 2013. Eleven months later, the Court is ready to try again.

One need not be terribly cynical to wonder why the Court is so insistent.

I smell a rat.

Friday, October 17, 2014

A thought on Public Opinion, Marriage Equality and the Court

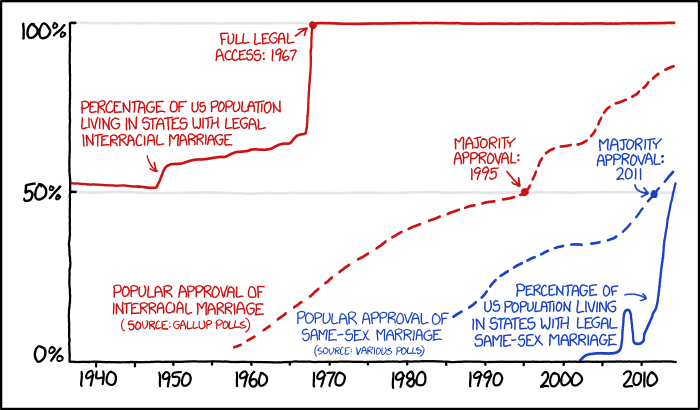

A few days ago, a student referred me to the following graph:

The graph raises two questions for me. The first and most glaring question is the gap between the red lines, between public opinion on interracial marriage and the percentage of people who lived in states that allowed the practice. To be sure, this explains Naim v. Naim and the Court's refusal to strike down anti-miscegenation laws as discordant with Brown and equal protection. But what it does not explain is the Court's decision in Loving, which struck down these laws in the 16 states that still had laws in the books against interracial marriage. It seems the case cannot be explained by pointing to public opinion in 1967. It also cannot be explained as a time when the Court rounded up a few remaining outliers.

Could the case be explained by invoking morality and constitutional principles? If not, what is left?

The second question focuses on the lag between opinion on marriage equality the number of states approving the practice. That the blue lines are about to meet sometime soon tells us something important about the rapidity with which the marriage equality debate has moved in the last few years. To me, the question is: what accounts for that change? Can we explain it simply by pointing to social movement theory?

This leads me to a third question, about which I will have much more to say in a future post: why did the Court hesitate last week and decide against entering the marriage equality debate? To enter the debate would be to side with a majority of the American public. It is also true that a majority of the population now live in states that issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The writing is clearly on the wall. So why wait? How strong must public opinion be on this question? How many outliers must remain?

Part of the answer must be that we misunderstand what the Court is, what it does, and what it can do. We have a romantic view, fostered by the media and taught in many law schools, of the Court as a countermajoritarian hero. This is not an accurate view of the Court and its work. The Court is far from a fearless defender of the rights of minorities. In fact, the Court seldom leads public opinion but follows it. Rather than looking at the Court's hesitation from last week and asking why it chose not to decide, the better question is: how much more will it take for the Court to get in the marriage equality debate?

The graph raises two questions for me. The first and most glaring question is the gap between the red lines, between public opinion on interracial marriage and the percentage of people who lived in states that allowed the practice. To be sure, this explains Naim v. Naim and the Court's refusal to strike down anti-miscegenation laws as discordant with Brown and equal protection. But what it does not explain is the Court's decision in Loving, which struck down these laws in the 16 states that still had laws in the books against interracial marriage. It seems the case cannot be explained by pointing to public opinion in 1967. It also cannot be explained as a time when the Court rounded up a few remaining outliers.

Could the case be explained by invoking morality and constitutional principles? If not, what is left?

The second question focuses on the lag between opinion on marriage equality the number of states approving the practice. That the blue lines are about to meet sometime soon tells us something important about the rapidity with which the marriage equality debate has moved in the last few years. To me, the question is: what accounts for that change? Can we explain it simply by pointing to social movement theory?

This leads me to a third question, about which I will have much more to say in a future post: why did the Court hesitate last week and decide against entering the marriage equality debate? To enter the debate would be to side with a majority of the American public. It is also true that a majority of the population now live in states that issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The writing is clearly on the wall. So why wait? How strong must public opinion be on this question? How many outliers must remain?

Part of the answer must be that we misunderstand what the Court is, what it does, and what it can do. We have a romantic view, fostered by the media and taught in many law schools, of the Court as a countermajoritarian hero. This is not an accurate view of the Court and its work. The Court is far from a fearless defender of the rights of minorities. In fact, the Court seldom leads public opinion but follows it. Rather than looking at the Court's hesitation from last week and asking why it chose not to decide, the better question is: how much more will it take for the Court to get in the marriage equality debate?

Saturday, October 11, 2014

The Court on Gay Marriage

Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear appeals from five states that sought to ban gay marriage. The Court also declined to explain why. This led supporters of gay marriage to hail the Court's non-action. But not everyone agreed that this was a good thing.

Critics made the obvious arguments. According to Professor John C. Eastman, it was “beyond preposterous” for federal courts to define marriage. This was a question that must be left to the political process. But what would he make of the Court's view, expressed in 1967, that "[t]he freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men"? Or the recognition that "[m]arriage is one of the 'basic civil rights of man,' fundamental to our very existence and survival." The case was Loving v. Virginia.

I also wonder what he might say about the Supreme Court short-circuiting the political process in Shelby County. I wonder.

Progressives also were not unanimous in their approval. One argument in particular caught my attention. This was from Slate's Dahlia Lithwick:

Regardless of the answers, the court should not be in the business of gingerly surfing public opinion until it’s safe enough to ride that wave into shore. And by waiting (or even talking publicly about thinking about waiting) for the majority of Americans to climb on board before ruling, the court is failing at its most vital task: protecting civil liberties from majorities not inclined to wait. The court hardly becomes more legitimate by suggesting that it will decisively do the right thing once it’s been done. And as of Monday, it’s been done.Lithwick is asking the Court to play the role of countermajoritarian hero. But we must ask, has the Court ever played this role in American history? This is a game I often play with my students: think of a case when the Court in fact played this role, and let's think about how it was possible. Brown is often the first answer they think of, and it is often the only one. They don't often think of Brown II, or Naim v. Naim, or Eisenhower and the Little Rock Nine, or the March on Washington, or Freedom Summer. rather, they think of Brown in a vacuum. And that is not only misguided, but it is also a mythology of the Court that we should not foster.

Think of this: could we view the Court inevitable reconsideration of the Second Reconstruction as an instance when the Court will be performing "its most vital task"? I suspect that Professor Eastman would encourage the Court to do precisely that. And if so, what does that tell us about the Court's role? Could our perceptions be clouded by nothing as crass as whose ox is being gored?

College Board, AP Testing, and Ideology

I must begin with a confession: I am not a fan of standardized tests. I am also not a fan of the College Board, or of AP classes in general. That said, I have followed with great interest the debate in Colorado over curricular changes in AP American history courses. A few days ago, an entry from the N Y Times editorial page editor's blog included a link to a full practice test based on the new AP curriculum. And yes, I got curious.

The questions were fairly bland and straight-forward. Nothing really jumped out at me (though maybe that's the point, a critic might argue). Until I came to page 13.

Labels:

AP History,

College Board,

Colorado school board

Friday, October 10, 2014

As Hobby Lobby Collides with the End of the Second Reconstruction Through the Fair Housing Act

A week ago, the Court granted cert in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, Inc. The case involves a challenge to the allocation of low-income housing tax credits under the Fair Housing Act. The narrow question for the Court is whether the Fair Housing Act recognizes disparate impact claims. But a far more important and far-reaching question lies in the background of the case: what is the constitutional status of disparate-impact claims?

Put this way, this question takes me to the end of last Term and Hobby Lobby. While the case was hailed at the time as either a victory for religious freedom or an attack on women's health care, a crucial aspect of this debate has gone almost unnoticed: how Justice Alito's opinion for the Court appears to short-circuit the ongoing conservative project to end the Second Reconstruction.

Tuesday, May 6, 2014

Making Sense of Schuette; or, it might be time to give back the 14th Amendment

In the wake of Grutter v. Bollinger, Michigan voters approved Proposal 2, a measure designed to prohibit the use of race in admission to state universities. It stood to reason that the Roberts Court would uphold this proposal, and so it did, in the recent Schuette v. BAMN. According to the plurality opinion, authored by Justice Kennedy, this case involved a fundamental right held "by all in common:" "the right to speak and debate and learn and then, as a matter of political will, to act through a lawful electoral process."

I wonder what he means by that. Assume that citizens of the state of Michigan return to the polls ten years from now and reverse Proposal 2. Assume, that is, that they continue todebate, learn, and act once again through a lawful process. What if the citizenry takes it further and in fact demands that state universities take race into account during their admissions processes? What would the plurality say then?

This is when our bizarre constitutional world kicks in. Opponents of race conscious policies can eliminate these policies through the political process and the Court stands aside. Were supporters of these policies able to overturn this outcome through the same political process, the Court will be ready to stand in their way, in the name of constitutional justice.

This is a perverse constitutional world. If this is what the 14th Amendment demands in fact, it must be time to give the Amendment back.

How does anyone committed to an originalist jurisprudence make sense of this?

Better question: is there anybody left in the world who believes that our race jurisprudence is guided by law and not ideology and the justices' personal preferences?

I wonder what he means by that. Assume that citizens of the state of Michigan return to the polls ten years from now and reverse Proposal 2. Assume, that is, that they continue todebate, learn, and act once again through a lawful process. What if the citizenry takes it further and in fact demands that state universities take race into account during their admissions processes? What would the plurality say then?

This is when our bizarre constitutional world kicks in. Opponents of race conscious policies can eliminate these policies through the political process and the Court stands aside. Were supporters of these policies able to overturn this outcome through the same political process, the Court will be ready to stand in their way, in the name of constitutional justice.

This is a perverse constitutional world. If this is what the 14th Amendment demands in fact, it must be time to give the Amendment back.

How does anyone committed to an originalist jurisprudence make sense of this?

Better question: is there anybody left in the world who believes that our race jurisprudence is guided by law and not ideology and the justices' personal preferences?

Labels:

14th Amendment,

Affirmative Action,

Race,

Schuette

Wednesday, April 2, 2014

A word on McCutcheon and the Court that Politics has Given Us

The U.S. Supreme court issued this morning its long-awaited opinion in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission. The result surprised no one. Under federal law, an individual could could give $5,200 to a candidate over a two-year election cycle, yet no more than $48,600 as a whole. This meant than an individual could give to only 9 candidates in order to comply with the law. Similarly, federal law imposed an "aggregate limit" of $74,600 on contributions to all political parties and political action committees.

No longer.

In a 5-4 decision, the Court struck down these "aggregate limits" as unconstitutional under the First Amendment. In an opinion authored by Chief Justice Roberts, the Court could find no governmental interest that would justify these aggregate limits.

Commentators will have a lot to say about this case, even though there is very little new here. We have seen this before. The money line comes from Justice Breyer's dissent, right at the end:

Every time I read one of the doozies from the Roberts Court, I am reminded of Philip Kurland snarky yet paradoxically delightful Harvard foreword, published in 1964. The closing is remarkable in many ways. Take a look:

In the meantime, the law reviews will continue to pretend that there is a legal logic to all of this, and that the conservative majority is playing by the rules laid down. But there is clearly a much different story at play. This is not law as reasoned elaboration, but law as power. This is Thrasymachus, not Socrates.

Whatever happened to judicial restraint and the famed countermajoritarian difficulty?

I am being facetious, of course. Here's what happened: critics of the Warren Court won elections, took over the Court, and are now reaping the benefits. Judicial restraint plays no role in this story. Not that there's anything wrong with that. But at least let's call it what it is.

This leaves me with two questions. The first looks to the recent past, and particularly to the 2000 Election. For those who thought that Bush and Gore were one and the same, I wonder what they think about the Roberts Court.

The second question is for the Court's cheerleaders, those who find themselves today on the right side of 4. Do they really believe that they are fighting, as Randy Barnett wrote, "to save the Constitution for our country?" Do they really believe, as Jim Bopp wrote in a press release after the McCutcheon, that the ruling is "a great triumph for the First Amendment"?

Better question: had these great champions of the Constitution been around in 1964, what would they have said then?

We can only wonder.

No longer.

In a 5-4 decision, the Court struck down these "aggregate limits" as unconstitutional under the First Amendment. In an opinion authored by Chief Justice Roberts, the Court could find no governmental interest that would justify these aggregate limits.

Commentators will have a lot to say about this case, even though there is very little new here. We have seen this before. The money line comes from Justice Breyer's dissent, right at the end:

The result, as I said at the outset, is a decision that substitutes judges’ understandings of how the political process works for the understanding of Congress; that fails to recognize the difference between influence resting upon public opinion and influence bought by money alone; that overturns key precedent; that creates huge loopholes in the law; and that undermines, perhaps devastates, what remains of campaign finance reform.Tell me if you haven't seen this before. The template could not be any clearer. This is Shelby County redux. Remember how in Shelby County, the Court essentially substituted its views about racial discrimination in voting for the record compiled by Congress, a record with which it refused to engage? Remember also how Shelby County bootstrapped arguments made in dictum in a prior case -- Namudno v. Holder -- and then passed them along as settled law? Remember also how Shelby County overturned key precedents while pretending to do no such thing? And finally, who could forget that Shelby County undermined -- nay, devastated -- the crown jewel of the civil rights movement?

Every time I read one of the doozies from the Roberts Court, I am reminded of Philip Kurland snarky yet paradoxically delightful Harvard foreword, published in 1964. The closing is remarkable in many ways. Take a look:

The time has probably not yet come for an avowal that, in the field of public law, "judicial power" does not describe a different function but only a different forum and that the subject of constitutional law should be turned back to the political scientists. These students of political affairs realized, before lawyers did, that the true measure of the Court's work is quantitative and not qualitative. The Court will continue to play the role of the omniscient and strive toward omnipotence. And the law reviews will continue to play the game of evaluating the Court's work in light of the fictions of the law, legal reasoning, and legal history rather than deal with the realities of politics and statesmanship.I wonder what Kurland -- the preeminent conservative critic of the Warren Court -- would say about the Roberts Court. We have an idea. When he testified during the Bork hearings, he said the following about stare decisis: "But once the Court has rendered its decision, I think that the fact that it is based on erroneous reasoning or poor precedent or doctrine does not in any way make it an invalid, unconstitutional or reversible opinion for that reason." The Roberts majority has decidedly different ideas.

In the meantime, the law reviews will continue to pretend that there is a legal logic to all of this, and that the conservative majority is playing by the rules laid down. But there is clearly a much different story at play. This is not law as reasoned elaboration, but law as power. This is Thrasymachus, not Socrates.

Whatever happened to judicial restraint and the famed countermajoritarian difficulty?

I am being facetious, of course. Here's what happened: critics of the Warren Court won elections, took over the Court, and are now reaping the benefits. Judicial restraint plays no role in this story. Not that there's anything wrong with that. But at least let's call it what it is.

This leaves me with two questions. The first looks to the recent past, and particularly to the 2000 Election. For those who thought that Bush and Gore were one and the same, I wonder what they think about the Roberts Court.

The second question is for the Court's cheerleaders, those who find themselves today on the right side of 4. Do they really believe that they are fighting, as Randy Barnett wrote, "to save the Constitution for our country?" Do they really believe, as Jim Bopp wrote in a press release after the McCutcheon, that the ruling is "a great triumph for the First Amendment"?

Better question: had these great champions of the Constitution been around in 1964, what would they have said then?

We can only wonder.

Thursday, February 27, 2014

Gobbledegook Scholarship

The law review process is a bit -- how to say this politely -- unorthodox. Students with no expertise in the issues at hand make editorial decisions on articles that they may not even understand. Defending this process is not easy. It is an accident of history and not much more.

The question is whether the alternative is any better. Here's an example: three MIT graduate students created a computer program to write gobbledegook and pass it as scholarship. Academic conferences proceeded to accept the papers. And academic presses in fact published them.

I'll be sure to show this piece to my smug friends on the other side of campus. I might even direct them to the software itself, which available for free online.

Labels:

gobbledegook,

law reviews,

scholarship

Wednesday, February 26, 2014

There He Goes Again . . .

The Savannah, Georgia of the late 1950's and early 1960's was a cauldron of Black political activism. Many organizations, from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the NAACP to the Chatham County Crusade for Voters led voter registration drives, economic boycotts, and demonstrations against segregated public facilities. In 1963 alone, Blacks in Savannah had mass meetings every Sunday in order to drum up support for the movement. On July, 12, 1963, tensions erupted and 2000 Black demonstrators were scattered with tear gas and water hoses. In 1965, during the voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, 650 Blacks in Savannah held their own march as a show of solidarity.

It is clear to anyone paying attention that Savannah, Georgia played host to a very rich and very active civil rights community.

Not so, however, to Justice Thomas. As he recently told an audience at Palm Beach Atlantic University in West Palm Beach, Fla,

'My sadness is that we are probably today more race and difference-conscious than I was in the 1960s when I went to school. To my knowledge, I was the first black kid in Savannah, Georgia, to go to a white school. Rarely did the issue of race come up,'

We could try to make sense of what, at first blush, makes no sense. Dahlia Lithwick writes, for example, that

Maybe the issue never came up because color simply determined everything: where you could sip water, where you could swim, where you could go to school, which doctors you could see, which gas stations would allow you to use their restrooms. Maybe there was a lot less to talk about, not because nobody noticed racial differences but because the legal regime crafted to perpetuate those differences was omnipresent and seemingly impregnable.

But that's far too charitable. The question for anyone living through these tumultuous times is not whether the race issue ever came up. Rather, the question is how anyone could live through the Savannah, Georgia of the 1960's and remain unaware of the social and political revolution brewing.

This is the same man who could confidently say that there is no longer a need for the Voting Rights Act. We have a right to wonder, in light of these recent comments, how he knows this.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)